[ad_1]

On a humid monsoon afternoon in the early 1980s, in a village most Indians had never heard of, a Delhi artist stood silently before a mud wall. The village was Patangarh, deep inside the Mandla forests of Madhya Pradesh. The wall belonged to a modest Gond home. And on that wall, painted in earth pigments and improvised brushes, a teenage boy had created a world that seemed to move – snakes curling into rivers, birds morphing into trees, forest spirits floating above hills, every surface breathing with lines, dots and patterns.

The visitor, painter and thinker J Swaminathan, instantly sensed that this was not “tribal craft” or “folk ornamentation.” It had structure, language, confidence. It was, unmistakably, contemporary art. The boy was named Jangarh Singh Shyam. Within a decade, his work would travel from Patangarh to Bhopal, from Bhopal to Delhi, and eventually to Tokyo and Paris – carrying with it an idiom that came to be known worldwide as “Gond painting.” Those closest to him, however, insist that the truer name is “Jangarh Kalam.”

The forest, the hill and the painted wall

Long before the words “Gond painting” appeared in gallery catalogues or GI-tag notifications, there were just mud walls, red earth and the slow, attentive labour of village hands. In the forested belt of central India, in and around Patangarh in Madhya Pradesh’s Mandla district, painting was not a profession but a way of keeping faith with the world.The Gond and Pardhan communities who live here have long believed that every hill, river, tree and rock is inhabited by spirit. Art grew out of that belief. Images of tigers, peacocks, serpents, women, ancestors and deities were painted on the inner and outer walls of homes using what the land provided: charcoal for black, geru and other clays for warm reds and browns, chhui mitti for pale yellow or white, crushed leaves for green, plant sap and cow dung as binders.

These images were not “artworks” in the contemporary sense. They were part of rituals marking harvests, marriages, festivals and propitiations to Bada Dev, the Gonds’ great god. The practice — digna and bhitti chitra — sat alongside oral traditions: the songs of Pardhan bards, the sound of the single-stringed bana, the stories of origins, animals and gods. The aesthetic was functional, sacred and collective.What did not exist yet was a single, named, portable “Gond painting” style. Different villages had different motifs, and the marks on the wall faded with time, rain and replastering. The leap from wall to canvas, from ritual to recognised art form, would come much later — and decisively through one young artist from Patangarh.

From ritual markings to narrative art

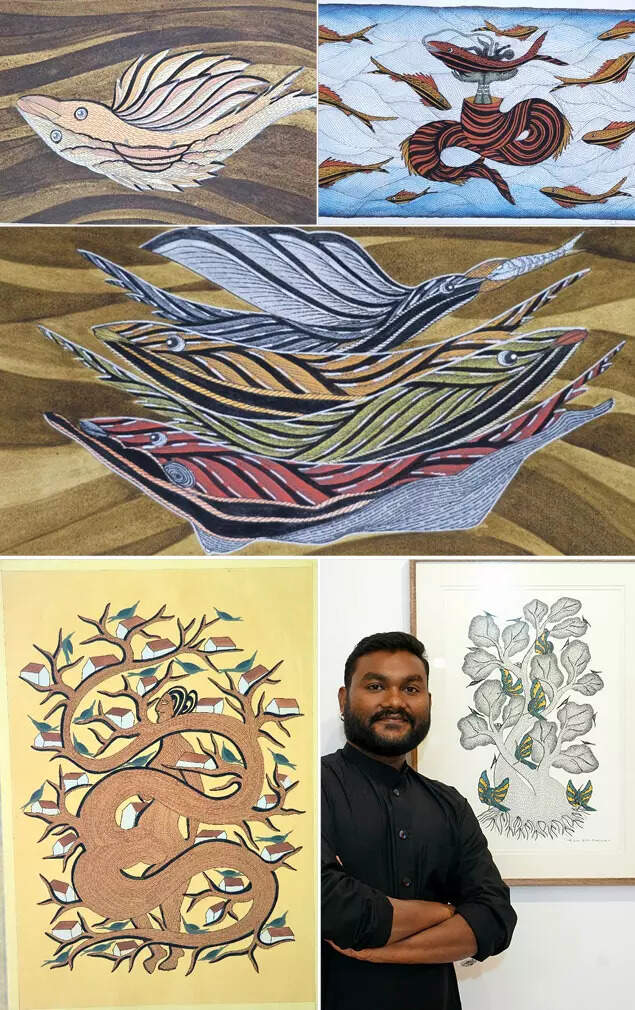

When we speak of Gond painting today, we are usually referring to a visual language built up from fine lines, dots and dashes, filling animal and human forms with pulsating pattern and colour. Horses, stags, fish, birds and trees are often shown in improbable combinations: a tree that is also a bird, a river that coils like a snake, a tiger whose body is made of leaves.These choices are not random decoration. They grow out of the community’s close observation of the forest, but they are also filtered through individual imagination and memory. As Mayank Singh Shyam, elder son of the late painter Jangarh Singh Shyam, explains of his father’s work:“This art emerged from my father’s soul and imagination, and on that foundation, it received the identity of a distinct style. The term ‘Gond painting’ is neither historically accurate nor rooted in our traditional practices. In India, artistic styles like Mithila, Madhubani, Warli, and Kalighat carry clear geographical identities. But Patangarh never received such recognition, and my father never called himself the creator of any ‘Gond’ style.”

His description underlines two important things. First, that what we now call Gond painting is rooted in older wall traditions, but is not simply a direct transfer of those motifs. And second, that the form in which the world sees it today was decisively shaped by one individual.“I call it the Jangarh Style, because this was a revolutionary and completely new artistic form born from my father, the late Jangarh Singh Shyam. For the first time, someone created a stylistic form based on tribal memory, experience and tradition. Before him, the mural markings and motifs in our region did not have an independent artistic identity.“If you read research papers from the 1970s, you will not find any reference to ‘Gond painting’. This name was assigned later, merely because an Adivasi artist had created paintings drawn from his imagination and life experience.”The boy whose imagination lifted that visual memory onto paper and canvas grew up in the very landscape he painted — in Patangarh, among hill slopes whose very name, many scholars point out, echoes the Dravidian root kond or konda for green hill.

The moment Patangarh entered the art map

The turning point came in the early 1980s, when the currents of urban modern art met the currents of tribal expression in Bhopal. The mediator between these worlds was J Swaminathan — painter, poet, Marxist intellectual and one of the key figures behind Bharat Bhavan, the multi-arts complex that opened in 1982.At Bharat Bhavan, Swaminathan set up the Roopankar Museum of Folk and Tribal Art with a clear conviction: that tribal and folk artists were not anonymous “craftspeople” but contemporaries of any modern painter, thinking in their own visual philosophies. To make that visible, he travelled widely through the tribal belts of Madhya Pradesh, looking for artists whose work broke the frame of mere ritual.

In 1981, that search brought him to Patangarh. On the mud walls of a house, he saw something that startled him: brilliantly imaginative scenes painted with a sureness of line that felt entirely personal rather than formulaic. The hand behind them was a teenager, Jangarh Singh Shyam.Swaminathan brought him to Bhopal. For the young painter, the move meant not just a change of geography but of medium and gaze. At Bharat Bhavan, he was given paper, canvas, brushes and poster colours. The walls of his childhood were replaced by surfaces that would not be plastered over. His images could now travel; they could be exhibited, sold, collected.In this new environment, the motifs of Patangarh began to expand. Birds and animals were no longer just auspicious elements in a domestic ritual; they became central protagonists in dense narrative fields. Trees grew bodies, gods inhabited forests, and the patterns of dots and lines began to act almost like musical notation — echoing the community’s bardic tradition in visual form.

Jangarh kalam: When a style finds its name

As these works began to circulate, critics and curators saw that something new was happening. This was not simply a documentation of tribal life for urban consumption; it was an authorial vision.Working at Bharat Bhavan, and later in other cities and abroad, Jangarh developed a distinctive technique: inner and outer contour lines drawn with great precision, and figures filled with comb-like strokes, rows of ovals, scales and squiggles that created an intense sense of movement. The surfaces of his paintings glowed with deep reds, electric blues and greens, bright yellows and speckled textures.The art world began to refer to this as “Jangarh Kalam” — the pen or style of Jangarh. Over time, however, as more artists from Patangarh and elsewhere adopted and adapted this vocabulary, the broader label “Gond painting” took hold, especially in the market and among urban buyers.For his family and many of his peers, this shift in terminology remains unresolved. The label “Gond painting” links the work to community identity, but it also risks erasing the very individuality that allowed it to enter the world in this form. Mayank voices that tension sharply:“People still look at traditional wall drawings and say they want the ‘traditional type of work’. They send me my father’s paintings as reference. They don’t know this is not tradition—it is a new style.“It is like salt—you cannot see it, but you taste it. You can see my father’s influence in every artist’s work. That essence is not Gond—it is Jangarh.”For the purposes of history, both terms now sit side by side: Gond painting as the larger field, Jangarh Kalam as a crucial, defining stream within it.

A village of painters

As Jangarh’s reputation grew, so did the number of brushes and Rotring pens in Patangarh. Young men and women from the village and the surrounding Mandla forests began training, first informally, then as apprentices. Some learnt directly from him in Bhopal or during his visits; others studied his works that travelled back home.Names like Anarkali Shyam, Champi Bai Shyam, Rajesh Shyam, Santosh Maravi, Sanjay Pancheshwar and many others emerged from this context. Their paintings transformed “traditional musical memory into imaginative contemporary visuals”, as one exhibition curator put it: fairytale-like images crafted out of fine lines, scales and dots that vividly express stories based on folklore and mythology. In these canvases, animals grow into trees, trees merge into forests that seem to reach the gods, and the human figure often appears small in a world dominated by nature.The shift from charcoal and mud pigment to acrylics and ink did not mean an abandonment of older themes. Instead, it allowed them to be archived, traded and displayed. Red began to stand for the heat of the sun, yellow for energy, green for the forest’s life, blue for calmness and tranquillity. The language of colour, once dictated by whatever the soil and leaves could provide, now also responded to market demands and exhibition lighting.At the same time, Gond painting retained a quality that set it apart from much urban art: a persistent refusal to place humans at the centre of the universe. Trees, tigers, elephants and peacocks are often the real protagonists. The paintings become both celebration and warning — quietly rebelling against deforestation, urban decay and the loss of habitat by insisting, again and again, on the primacy of the more-than-human world.

New stories, new mediums

While many Patangarh artists continued to work in a vocabulary close to Jangarh’s, others took seriously his advice that each artist must find their own way. Nowhere is this more visible than in the work of his daughter, Japani Shyam.She grew up literally at his side: “My father is my guru. I learnt painting from him. I was very young at that time, but I still worked with him. From time to time, he would teach me things while working on his paintings, and I would follow what he showed me.“The style comes naturally. Whoever learnt from him, you can see his influence in all their work. I have seen my father doing highly experimental work. He always said that every artist should create their own distinct style.”Watching him create dazzling, highly coloured works filled with detail, she chose to move in a visually opposite direction, without abandoning the underlying grammar.“My father always worked in very colourful compositions with a lot of detailing. Detailing has always been part of our work, but I felt that I should bring something different into my own work.“In traditional Gond painting, there are bright, vibrant colours and a lot of detailing. People recognise a Gond painting immediately. In the beginning, I also worked exactly like my father.“But remembering what he told all of us — ‘create your own style’ — I started working in just two colours, with a white background. At first, people could not understand it, because they were used to seeing Gond paintings in very bright colours. So black-and-white looked very different to them.“Gradually, I explained that the story is still the same, the same nature, the same themes — I only changed the colours and medium. That is how my work began to acquire a separate identity.”Her canvases often centre women and contemporary life as much as forests and animals:“In our traditional Gond painting, the focus is mainly on nature — trees, birds, animals. That still exists, but now I take ideas from what I see in front of me.“Whether it is the city, the village, or the lives of women — most of my work has been centred around women. I observe the surroundings where I live: city life, village life, what is happening in the present time, and I work on that.“Instead of creating long mythic stories, I now work on real things around me. That is what makes my work a little different from others.”In doing so, she embodies one of the most striking features of Gond painting today: its ability to remain rooted in ritual and nature while absorbing the pressures and textures of the present — from migration and urbanisation to gendered experience.

Lineage, labour and the question of authenticity

The growing popularity of Gond painting, especially in urban fairs and online platforms, has raised a familiar problem in folk and tribal arts: how to tell the difference between deep, rooted work and shallow imitation. Japani’s response to this is less about policing than about attention:“As you start understanding something deeply, you begin to recognise quality in one glance.“Today many people like Gond painting, but only a few truly understand it. On the internet, in fairs, there are many artists — some from our community, some not — all working under the name ‘Gond painting’.“Some people just think it is Gond painting, no matter who made it. But there are others who know the artist’s name, understand the story and what is actually being conveyed.“I think only those who have a genuine interest in art, and who know and understand it, can truly identify which work is deeper and distinct.”Her favourite works of her father say something about what that depth looks like: “It’s very difficult for me to choose five, because I love all of my father’s work. But personally, I especially love his works based on gods and goddesses.“The way he painted gods and goddesses — whether in drawings or colourful paintings — was entirely his own style. Their eyes, faces, mouths, noses, the jewellery, the adornment — everything was very detailed and imaginative.“Perhaps nobody imagined our deities like that before. But he created them through his imagination in such a way that they do not look frightening or wrong — just astonishing.”In those faces — neither sanitised nor terrifying — one can glimpse what made his work, and by extension Gond painting as we know it, so singular.

A journey that ended in Japan

If the story of Gond painting’s rise has the feel of a fairytale — a boy from a remote village discovered by a renowned modernist, his work travelling to museums in Tokyo, Paris and London — its central figure’s death remains a stark reminder of the vulnerabilities behind such trajectories.In 2001, while working in Japan, Jangarh died in circumstances that have since been described in official records as suicide. For his family, the questions around that moment remain raw. Mayank says simply:“This question has lived in my mind for 25 years. What happened with my father remains unanswered. Why did it happen in Japan, even though he had already travelled there twice earlier? Who facilitated his travel? Under what circumstances did everything unfold there? The truth is still unknown.“People say he was depressed, but we never knew of him taking any such medication. He loved us deeply. We could not even see him one final time—his body came home after ten days. We could not embrace him and cry.“It is the deepest wish of my mother, my siblings and mine that we go to Japan and light a lamp at the place where he breathed his last.”For the art, however, that journey from Patangarh to Japan left a lasting mark. Large murals in Japanese museums, international exhibitions in Europe and America, and high-profile sales turned Gond painting from an almost entirely local practice into a recognised category in the global art market.

Recognition, gaps and the role of the state

Despite this international acclaim, the recognition accorded at home has been uneven. Jangarh received the Madhya Pradesh government’s Shikhar Samman, and his works have entered major Indian collections. Yet, as Mayank points out, the scale of his contribution — creating an entire stylistic movement and opening a path for dozens of artists — has not been fully matched by institutional honour:“Despite creating such a revolutionary artistic movement, 25 years have passed and the government has given nothing beyond the Shikhar Award. The students he trained received honours. But the one who created the style did not. That is the biggest mistake.“We all artists believe that if this style is officially recognised as the ‘Jangarh Style’ or ‘Jan-Kalam’, it would be the greatest tribute to him.”Their demand is not only personal. It speaks to a broader question: can the state and the art establishment recognise individual Adivasi artists not merely as representatives of a community form, but as authors of styles and movements? The GI tag for Gond painting from Madhya Pradesh acknowledges geographic and community origin; what Mayank and others seek is a similar clarity around authorship within that field.

Why Gond painting still needs a new audience at home

Globally, Gond painting — especially works from the Jangarh lineage — enjoys a steady presence. Exhibitions in Paris, London, Tokyo and New York, illustrated books, collaborations with designers and international collectors have all kept demand alive. Mayank notes from experience:“In India, people still don’t fully understand how important this art is. I have just returned from exhibiting in Paris. Abroad, there is deep respect for it. But in India, awareness is still lacking. That is why media has a crucial role.”That role involves more than celebrating “tribal art” in occasional features or festivals. It means telling the story of how a village like Patangarh became a hub of contemporary practice; how women like Japani have taken the line and dot further into new subjects; how younger artists are using the Gond vocabulary to speak of climate anxiety, migration, caste and gender. And it means listening carefully when those within the tradition say that names matter — that “Gond painting” is not a flat, singular thing, but a field in which Jangarh Kalam occupies a defining place.From mud walls washed away each monsoon to canvases that hang in climate-controlled galleries thousands of kilometres away, the journey of Gond painting is not just a story of art. It is a story of how imagination travels: from a boy in a forest village painting what he sees and dreams, to a family and a community who continue to hold that line steady, even as the world looks on.

[ad_2]

Source link