[ad_1]

Bhima Madvi was last seen by his family being taken away by security personnel from their village, Rekhapalli, on December 4. Three days later, his cousin Sukram Madvi found him lying lifeless on a cot inside the security camp at Wattewagu.

The police claim Bhima, 46, died by suicide. But his family suspects he was beaten to death by the security forces.

Separated by about three km of forests, Rekhapalli and Wattewagu lie in Chhattisgarh’s Bijapur district, in a block called Usur. Until a few years ago, Usur was largely under the sway of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), the banned group that has been waging an insurgency in the forests of central and eastern India for decades.

The Maoists ran a parallel state in the villages of Usur, governing every aspect of life through a network of organisations and committees.

Since 2024, however, the state has aggressively expanded its presence in the area by establishing a grid of security camps, most of them manned by the paramilitary soldiers of the Central Reserve Police Force.

Of the 52 new security camps that came up in 2025 in Bastar, the region in southern Chhattisgarh of which Bijapur is a part, 22 were established in Bijapur. Seven of those came up in the Usur block alone.

Rekhapalli is now surrounded by two camps. The first came up in Kondapalli, three km away, across the Talperu river. It was followed a month later by the camp in Wattewagu, which according to local residents, houses the COBRA – Commando Battalion for Resolute Action – an elite anti-Naxal force within the CRPF.

In CRPF’s parlance, both the camps are called “forward operating bases” – set up with the purpose of “breaching the enemy’s core areas by sustained operations”.

The establishment of these camps, said residents of Rekhapalli and other villages within their operational radius, has forced the Maoists to retreat. With Maoist armed cadres no longer visiting the area, village-level Maoist organisations have ceased to function, and many lower-level Maoist functionaries have surrendered to the police, local residents said.

Effectively, as a young man put it, entire villages have come under a new kind of “command”.

As a result, security forces now frequently patrol the area.

It was during one such patrol – not the first – that CRPF personnel from the Wattewagu camp took away Bhima.

For the residents of Rekhapalli, his detention and death have underscored the radical change sweeping through the area – one that they say, has left their lives more unpredictable than before.

A contested death

A week after Bhima’s death, I travelled to Rekhapalli. It took me a four-hour bike ride from the district headquarters, via Awapalli town, cutting through thick teak forests and crossing half a dozen shallow water streams, to reach the village. Lying on the banks of Talperu river, it is a large village with 105 houses, spread across three hamlets.

Bhima lived with his mother, his wife, and four children in one of these hamlets, in a small two-room house enclosed within a large open space. Two tall palm trees swayed above, while hens, cocks and goats ran around the house.

On the morning of December 4, security forces showed up at the house, asking for Bhima.

“They entered the house with their shoes, threw open our granary, rumbled through the grain stock, threw out our belongings,” recounted Dewe Madvi, Bhima’s 75 year-old mother.

Bhima was not at home. His neighbour, Mangu Madkam, said the security forces beat him up, asking about Bhima’s whereabouts.

Claiming they had spotted a bullet shell lying near it, they also asked him to open a blue drum, Mangu said. They suspected the drum contained weapons and explosives.

Mangu said he refused to do their bidding. “What if they planted the explosives themselves and fixed a case against me,” he reasoned. He claimed that he had already spent a year and half in prison when the police booked him in a false case a few years ago. He was not willing to risk it again, he said, holding his two children close to him.

After about an hour, Bhima was found at his cousin Sukram’s house, where they had gathered to meet visiting relatives.

Mangu said the security personnel dragged him along with Bhima and another villager to separate spots in the forest. He was beaten up and asked to reveal where the Maoists had hidden their explosives – information that he said he did not have.

About two and half hours later, he and the other man were allowed to return home with their bruises. But Bhima was taken away. “That was the last we saw of him,” said Bhima’s wife, Pande Madvi, her voice choked with sobs.

When Sukram tried to intervene to stop Bhima being taken away, the officer leading the security patrol took Sukram’s phone and dialled his own number from it, asking him to contact him later. Sukram saved the number as “Cobra Sahab”.

The family called the officer several times over the next two days, requesting him to release Bhima. The officer asked the family to come to the Kondapalli market on December 6, but when they went there, no one showed up, Sukram said.

Instead, the next day, he was summoned to the Wattewagu camp. There, he found Bhima dead.

In a letter she wrote to the governor of Chhattisgarh, Bhima’s wife has asked for “a high level judicial probe” into her husband’s death. She suspects that Bhima was beaten to death by CRPF personnel.

Asked for comment, the CRPF officer heading the Wattewagu camp said that he had already given a written statement to the magistrate. He refused to respond to further questions, or even disclose his name, before disconnecting the phone call.

The police superintendent of Bijapur district, Dr Jitendra Yadav, told Scroll that Bhima had died by strangling himself with his own towel. He suspected it could be because Bhima had helped the police identify spots where the Maoists had hidden their weapons and therefore, feared reprisals from the insurgents. He confirmed that a magisterial enquiry into Bhima’s death was underway.

The superintendent also claimed that Bhima was “a lower-rung sangham sadasya” – member of Maoist village committees – who had turned over and “helped the police in many ways in the past”.

Sukram denied the allegation. “Bhima lived in the village, he never went out,” he said.

A slew of surrenders

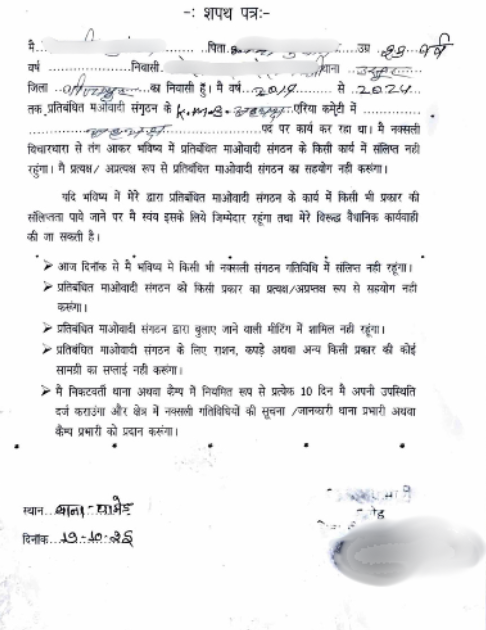

Three months before Bhima died, seven people in Rekpalli had surrendered to the police, admitting that they were members of a village committee that had actively supported the Maoists.

The decision to surrender was taken collectively in a public meeting held in Rekhapalli, said Unga Sodi, the village chief.

The seven included six men and one woman. The village residents felt it was best that they surrender to the police to prevent harassment of others by the security forces who would come looking for Maoists in Rekhapalli.

But were the seven people Maoist cadres, I asked. Armed cadres do not live in the villages, responded Sodi Bami, one of the seven members of the now-defunct village committee. He explained that when armed cadres visited, he and the other members of the village committee would support them by arranging food for them, keeping vigil and organising meetings. The committee members never acted on their own, he said. They relied on the armed cadres and leaders to provide them direction.

With the armed cadres no longer visiting Rekhapalli, Bami added, the committee no longer had a role to play in village affairs.

Bami also recounted how they surrendered to the police. Thinking it was safer to surrender in neighbouring Telangana, four of them travelled to Bhadrachalam on October 12. But Telangana Police handed them over to Chhattisgarh Police. The three others who followed them were intercepted even before they reached Telangana.

The woman member was sent back home the next day with a letter testifying that she had surrendered at the Pamed police station. But the six men were subjected to a week of questioning, Bami said. Later, they were sent to Bijapur district headquarters where they were given vocational training for a month before being allowed to return home. They were neither given a training certificate nor a surrender document, he added.

Back in the village, the group hoped that their brush with the police was over and they could return to a quiet life. But in November, the security forces showed up in the village asking for those who had surrendered. They also asked for Bhima Madvi, said Mangu Madkam. Bhima was not around – he had gone to another village to attend a relative’s funeral.

The village residents said they had no idea why the security forces were interested in Bhima. In November 2024, too, they had detained Bhima along with several others for the village, subjecting them to a week of questioning before they were released, Rekhapalli residents recounted.

Explaining why the security forces were frequently visiting Rekhapalli, Bijapur police superintendent Yadav said that intense surveillance was necessary in villages that had been under the shadow of the Maoists for about four decades. It was important to keep tabs on those who had surrendered, he said, since according to the police’s intelligence network, these areas are still being visited by the Maoists.

But doesn’t this put those who have surrendered at risk, I asked Yadav. In 2025, the Maoists had killed 27 civilians in Bijapur, including contractors and villagers, while 33 civilians were killed in 2024. It was not clear how many of these were linked to the surrenders.

Those who have surrendered are cautioned against immediately returning to their villages, the police superintendent said. Instead, they are advised to look for work in nearby towns until the police can free the area of Maoist presence, he said, adding that the state was making steady progress towards that goal. Bijapur district, with roughly 600 villages, now had 108 security camps to support anti-Maoist operations. “We have so far penetrated 170 villages of Bijapur, which was unthinkable a few years ago,” Yadav said.

The same question was put to the residents of Rekhapalli and nearby villages – was it not risky for those who had surrendered to return home? The response was categorical: those who have surrendered with the consent of the villagers are not harmed.

“Only those who surrender secretly, face a threat,” said Nagesh Punnem, the sarpanch of Nela Kanker panchayat that includes Rekhapalli and three other villages.

He cited the example of two people in Nela Kanker who had been killed by the Maoists in October 2025 because they had surrendered secretly and were suspected of being police informers.

Thirty-three others from the Nela Kanker panchayat who had surrendered to the police in the last two years – with the consent of the villagers – had come back to live a regular life without facing any trouble from the Maoist party, Punnem said.

But they faced harassment from the security forces, said several of those who had turned themselves in. Well after they had surrendered, they continued to be summoned to the police station to mark their presence every week. And the security forces continued to periodically come to their villages to check on them.

Beatings followed by treatment

There was a reason why security patrols were not welcome, local residents explained.

In Komatpalli, a village near Rekhapalli, residents recounted what they had experienced on December 4, the day Bhima was picked up. That day, security personnel from Wattewagu camp also visited their village, said Laxman Madvi, a resident of Komatpalli. He alleged that the security forces beat up several villagers and took two men away.

The next morning, when villagers went to the camp to request for the release of the two men, the camp authorities asked them to take those injured in the beatings the previous day to the Kondapalli field hospital for treatment. The hospital exists inside the CRPF camp at Kondapalli.

Some of the injured people had to be carried on cots to Kondapalli since they were unable to walk, Ladman Madvix said. They were administered injections, but no written medical records were shared with them.

“Maar kar ilaj bhi karte hain” – they first beat us up and then treat us – laughed the villagers.

This was not the first time that security forces had beaten them up, said a panchayat member who requested anonymity.

In October, when Komatpalli had celebrated Nuka Pandum, a pre-harvest festival, security forces had surrounded the village and beaten up nearly 30 men, including the village gayta and pujari – healer and priest – who were conducting the rituals, said several residents.

Scroll attempted to seek a response about these allegations from the officer heading the Wattewagu camp but he disconnected our phone call.

According to residents of Komatpalli, in November alone, security personnel had patrolled their village and its forests and farms three times. Each time someone was beaten up, they alleged. “We don’t run away, but they stop and question us on the movement of the Maoists. If we say we do not know, they beat us up,” said the panchayat member.

Frequent CRPF patrols were making it difficult for them to work in their fields without fear, the village residents said. This had disrupted the busy agricultural season when Adivasi farmers harvest and thresh grain.

Earlier in the year, they had suffered an economic setback during the tendu patta season. The collection of tendu leaves, which are used to roll country cigarettes called beedis, is a major source of income for the Adivasis of southern Chhattisgarh. In 2025, the state government banned private contractors from the trade and tasked the forest department with directly purchasing the tendu patta from the collectors and depositing the money in their accounts. But since most people in Bijapur’s Usur block do not have bank accounts, they were unable to participate in the trade.

Uncertain futures

Tumirguda, home to about 35 families, is one of the three hamlets of Rekhapalli.

Ramesh Madvi, a resident of Tumirguda, said that 14 men from the hamlet were currently in prison, facing a slew of Maoist-related cases. Their families were under severe financial strain, unable to bear the legal costs to fight the cases that continue to drag on.

In Bhima Madvi’s house, there were other worries.

While his three daughters lived in the village, his son was enrolled in Class Five in a government residential school in the Usur block headquarters. He had rushed back home hearing the news of his father’s death.

Sukram, Bhima’s cousin, who is a college graduate, expressed concern about his nephew’s future. “I do hope he is able to resume his studies later,” he said.

All photographs by Malini Subramaniam.

[ad_2]

Source link